- Home

- Index

- Introduction

- Object description and manufacturing process

- The origin of the goblet and its craftsmen

- Inspiration drawn from nature

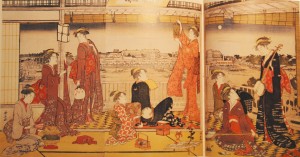

- Inspiration and objects of comparison from Japan

- Inspiration and objects of comparison from other parts of Asia

- Inspiration and objects of comparison from Europe

- Inspiration and objects of comparison with European roots in Japan

- The collector and the goblets way from Japan to Europe

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Table of Figures

- Files

The Hakone Goblet